The Past (Labar Zizigu) 1

The first known written reference

to the Margi appears in the chronicle of Henrich Barth (1857). His criteria of

identification are unspecified, and they seem largely defined in terms of

language. It is clear from his work that there was a "Marghi"

language--he collected vocabulary (Benton 1912, cf. Hoffman 1963:8-9)--and that

there were speakers of this language living along the border between Bornu and

Adamawa.

He first encountered Margi some

twenty miles north of Mulgwe] where they were described as having "adopted

Islam and become subjects of Bornu"(1857, II: Map facing 351), but by the

time he reached Mulgwe, where he collected the vocabulary, he was among

independent Margi, and his map of the area from Mulgwe southward to Uba is

labeled, "Marghi, a pagan tribe." The fact that Barth found speakers

of a language known as Margi does not, however, necessarily mean that the

speakers had a strong self-recognized identity. There are four points of

evidence that suggest that Margi-ness was not necessarily a mutually recognized

quality.

First, clan histories emphasize

distinctiveness and reveal diverse origins; second, the journal (1912-27) of

Hamman Yaji, a Fulani administrator of some of the Margi, makes not one

reference to "Margi," referring instead to numerous

"tribes" using names of localities; third, my oldest informants agree

that as youths their loyalties were local and they were more likely to identify

themselves in clan or geographic terms; finally, the more mountainous inhabitants

of the Mandaras immediately east of the Margi still have localized names, viz.

Sukur, Vemgo, Wogga.

The term Margi is then a label

applied to an imprecise population, whose history would be easier if their

identity were clearer. There are three different ways one might speak of the

history of the Margi. There would be first the general sweep of events in the

area as a whole; secondly, there would be the histories of the several

indigenous political units located within the area, and finally there would be

the histories of the different patrilineages, called fal, located 47 within the

region.

In practice, it is only the

latter which conforms with the Margi notion of labar zizigu (words of long

ago), and it is from these individual histories that all other history is

derived. This fact is significant, for although the political units became of

unquestioned dominance, the unit of history remains the much older clan.

Reckoning history in this fashion is indicative of the segmental tendency which

is characteristic of the societies of the Mandara Mountains, The centralized

political dynastic tradition is relatively recent--probably no more than 500

years old—and has not generated a centralized concept of history.

Although some events in the last seventy-five years such as wars and raids are parts of the traditions of numerous clans, it is nonetheless difficult to reconstruct the history of even a single political unit which is more than the history of the royal clan, and it will take a major ethno-historical enterprise to write a history of all Margi which is more than gross generalization.

The first suggested picture of

general Margi history was offered by C. K. Meek in 1931 when he discerned three

different "strata" which he identified as

(1) "indigenous peoples

(using this term of course in a purely relative sense),"

(2) a "Pabir stratum"

from the west, and

(3) a Kanuri line, identified

among Margi as "Gadzama" who claim to come ultimately from the old

Kanuri capital Ngasar-Gamo but more recently from the town of Mulgwe in Bornu

(1931, I:214- 15).

This outline seems basically sound though

superficial, for if the clan histories in each of the three strata is examined

the picture becomes far less distinct. Further, it would appear that all three

had a common origin, as there are indications that the movement of population

has been almost exclusively from the highlands of northern Cameroon to the

east. However, it should be noted that this movement has been sporadic and

sometimes so circuitous that Meek's notion of unrelated traditions is not an

unreasonable conclusion.

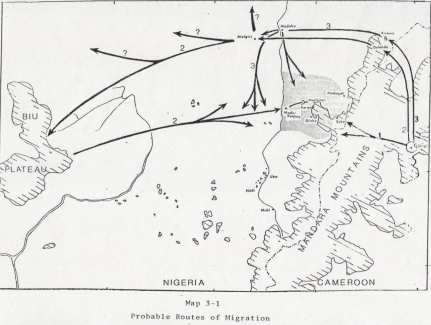

There seem to have been three

main routes (Map 3-1) of migration into the area occupied by Margi which

probably gives rise to Meek's three strata. There was one route directly into

the Map 3-1 49 area from the Cameroon plateau to the southeast, and it is

probably this which was taken by the groups Meek calls the indigenous peoples.

However, these clans came piecemeal over a long period and show contrasting

customs. They lacked any political authority beyond the clan, although later a

dynastic tradition also followed this route, a fact apparently unrecognized by

Meek. A second route of migration went north to Mount Gelabda (Golabda in local

pronunciation but Delabeda and Dalantuba in Barth's description of the Mandaras

[1857, II:369] and Seledeba or Zeladuva on some maps) and Mount Kirawa, the

northernmost prominence of the Mandara chain, thence westward and south into

the area of the Biu Plateau where they were influenced by the Pabur, and

finally turned eastward into what is now considered Margiland.

These groups have dynastic

traditions which, though showing Pabur influences, could be of Cameroonian

origin. This is probably Meek's second stratum. Finally, some clans which

followed this northerly route did not go as far as the Biu Plateau, instead

they settled around Madabu (Mutube) and Mulgwe where they came under the

influence of the Kanuri, or Vwa as they are called by Margi. Barth passed

through this area and mentioned its Kanuri influences. Some of these clans moved

south into the central and southern areas and constitute the

"Gadzama" tradition among the Margi.

Comments